The idea of robots living beside us no longer belongs to science fiction. They clean our homes, help care for older people, and even serve as companions for those who live alone. The presence of machines in ordinary spaces raises practical and social questions about how much of daily life can or should be shared with technology. Some people notice this change in entertainment spaces too, such as in a big small game casino, where the experience of play is driven by algorithms and automation rather than human staff. The line between mechanical work and human experience keeps getting thinner.

The Long Road from Industry to Home

Robots were not built for homes at first. Their origins are in factories, where they handled welding, lifting, and assembly. These early systems had no intelligence; they followed fixed instructions and worked in closed spaces to avoid harming people. Over time, advances in sensors, computing power, and machine learning made them safer and more flexible. Once the cost of these parts dropped, companies began building smaller machines for personal use.

When the first cleaning robots appeared, many people saw them as novelties. Yet over the years, they have become a quiet part of household maintenance. The lesson was simple: if a robot can do a dull or repetitive task, humans will make room for it. That principle now shapes how automation is spreading into other corners of life.

Work and Domestic Automation

Household robots represent a larger movement toward automated support. Beyond vacuuming, there are robots that assist with meal preparation, gardening, and even folding laundry. These devices rely on mapping, vision, and feedback systems that allow them to operate safely in unpredictable environments.

But what is interesting is not the technology itself, but how people adapt to it. In many homes, users adjust routines around the robot’s schedule. They tidy floors before cleaning robots start, or plan chores so that machines can handle certain steps. This blending of human and robotic effort changes how work is defined — less physical, more about coordination.

The same trend appears in workplaces. Offices use delivery robots, while hospitals depend on automated systems to move supplies. The focus is on freeing human time for tasks that require judgment or care, not just speed.

Care and Support for the Elderly

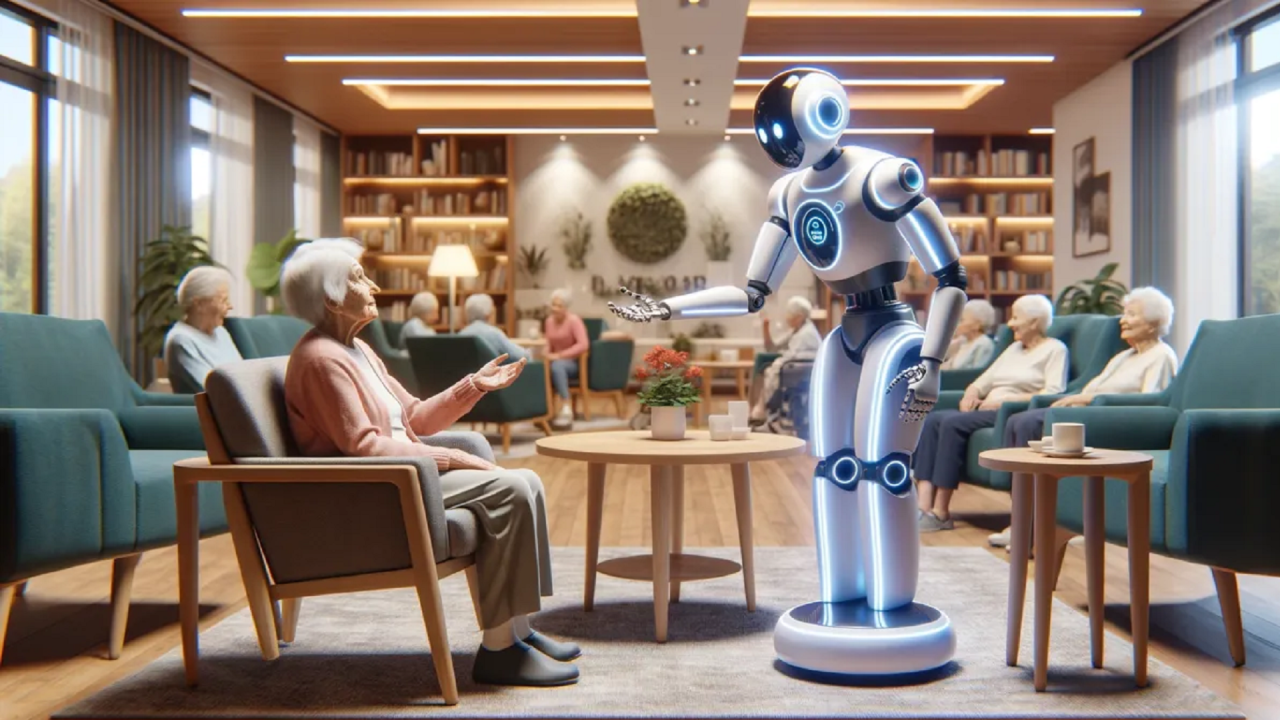

One of the strongest cases for robots today comes from the healthcare sector. Populations are aging fast in many countries, and the demand for caregivers is rising. Robots now help patients move, monitor vital signs, or remind them to take medicine. In some facilities, they act as companions for older adults who might not see family often.

This technology does not replace nurses or social workers, but it fills gaps. For example, a monitoring robot can detect a fall or an irregular heartbeat before anyone else notices. That kind of constant observation is hard for humans to maintain. However, relying on machines for care raises questions about trust, empathy, and privacy. When a robot becomes part of someone’s personal life, it collects data and observes routines — something that needs clear rules and oversight.

Education and Learning

Schools and training centers are also turning to robots as teaching aids. In language classes, robots help students practice pronunciation without judgment. In science and math, they offer hands-on ways to explore programming or problem-solving.

For younger children, the appeal lies in interaction. A robot can repeat lessons as many times as needed without frustration, offering consistent feedback. Teachers often use them as partners rather than replacements. This approach reflects a broader understanding: technology is most useful when it supports human work, not when it tries to imitate it completely.

Robots and Emotional Connection

The most complex form of robotic use is emotional support. Social robots are designed to respond to voice and movement, offering simple conversation and companionship. They are used with elderly individuals, people with anxiety, and children with autism. Some respond to touch, others recognize speech patterns and emotional cues.

The results vary. Many users form attachments, finding comfort in interaction that feels predictable and safe. Critics worry that such bonds replace human relationships with artificial ones. But supporters argue that if a person feels less lonely, the source of comfort might not matter. The key lies in balance — using robots to ease isolation while maintaining real social contact.

The Questions Ahead

As robots move into public and private life, the main challenge is not how to build them but how to live with them. They collect data, operate continuously, and can influence decisions about work, safety, and relationships. Society will need to decide how much control should remain in human hands and what kinds of decisions can be trusted to machines.

Economically, automation may reshape labor markets. Some jobs will disappear, others will shift toward maintenance, design, and oversight. Education systems will need to prepare people for this change, focusing on skills that are difficult to automate — empathy, creativity, negotiation, and ethical reasoning.

Conclusion

Robots are no longer tools we use occasionally; they are becoming part of the environment. Whether they clean a floor, deliver medicine, or talk to someone who feels alone, they extend what humans can do. But they also mirror our values and fears.

The future of robotics will depend on how societies define usefulness and control. Machines can take on routine work and even offer care, but the responsibility for meaning and choice will always rest with people. The partnership between humans and robots will continue to evolve — quietly, steadily, and perhaps more personally than we ever expected.